Current Programmes

Mauritania

“Great steps were taken towards peaceful co-existence at a local level. ... just yesterday, people still in conflict became mediators for surrounding villages.”

- An independent evaluator

Background

In Mauritania, we support two communities locked in a land dispute, helping them resolve it to mutual benefit. In 1989, nearly 100,000 Pulaar people were violently displaced from their homelands in the fertile Senegal River Valley. The land was given to Haratine people, ostensibly to help them out of modern day slavery. When the Pulaar returned, over 20 years later, returnees and Haratine both had a legitimate interest in the same land, with both acutely vulnerable to food shortages.

-

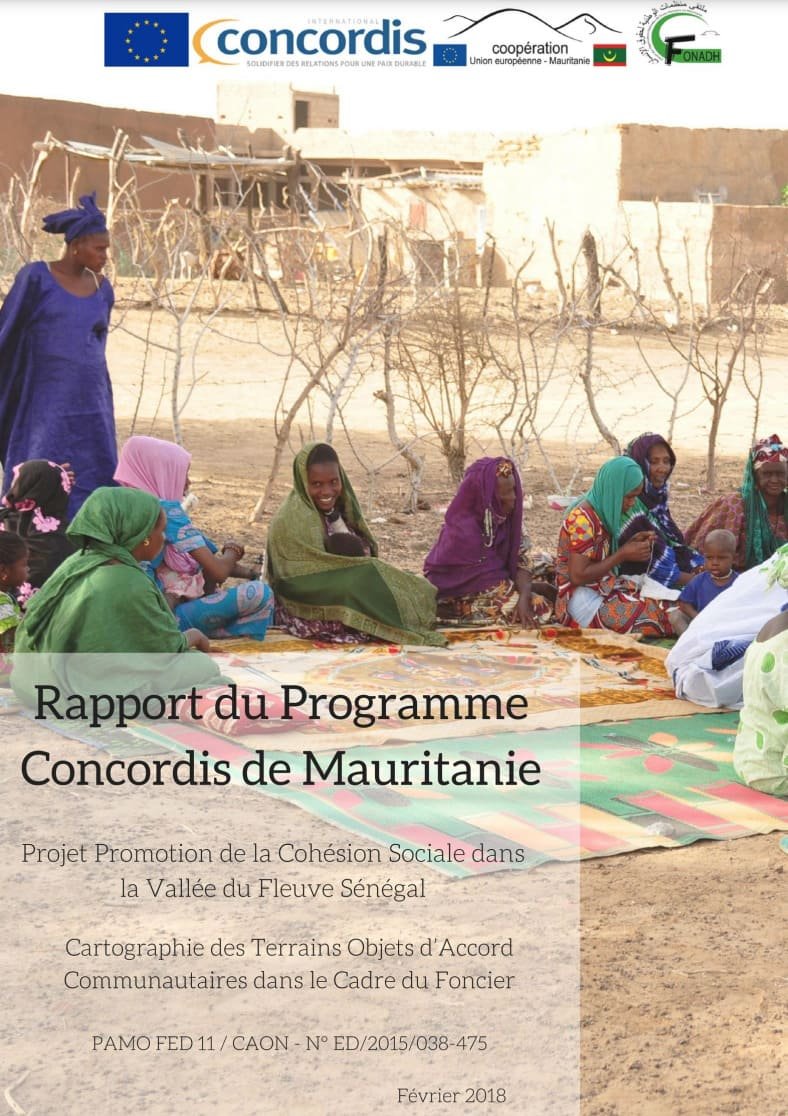

Most of Mauritania is a desert, supporting a substantial rural population and a growing urban one. The country’s southern border with Senegal has always been its most fertile region and a site of cultivation for centuries: these are the Walo floodplains of the Senegal River Valley. Left, Mbarek Diaw, Trarza, Mauritania, 2018

Unfortunately, the size and relative abundance of this region has led to tension over land ownership and rights of access between several different groups, each with competing interests and complex histories. The most acute conflict is between two particularly vulnerable groups: members of the Maur majority Haratine (the Haratine) and Afro-Mauritanian returnee refugees (the Returnees). The Returnees were forced to flee the country and dispossessed of their land in 1989, after social tensions arising from a political crisis between Mauritania and Senegal. Much of this abandoned land was passed on to the Haratine community by state authorities, in an effort to assist in their emancipation from the by-then outlawed traditional system of slavery.

Historically, the institution of slavery has deeply structured Mauritanian society. Although it was officially outlawed in 1981, slavery has left a legacy of societal inequality. While exact figures are disputed, remnants of slavery still have many social, political and economic implications for the descendents of former slaves in the country.

Since 2006, some 70,000 Black Mauritanian Returnees returned to the Senegal River Valley to find their former homes and lands claimed. This situation created resentment and tension on both sides, as Haratine groups had lived on the land for 25 years and could claim a legitimate sense of entitlement.

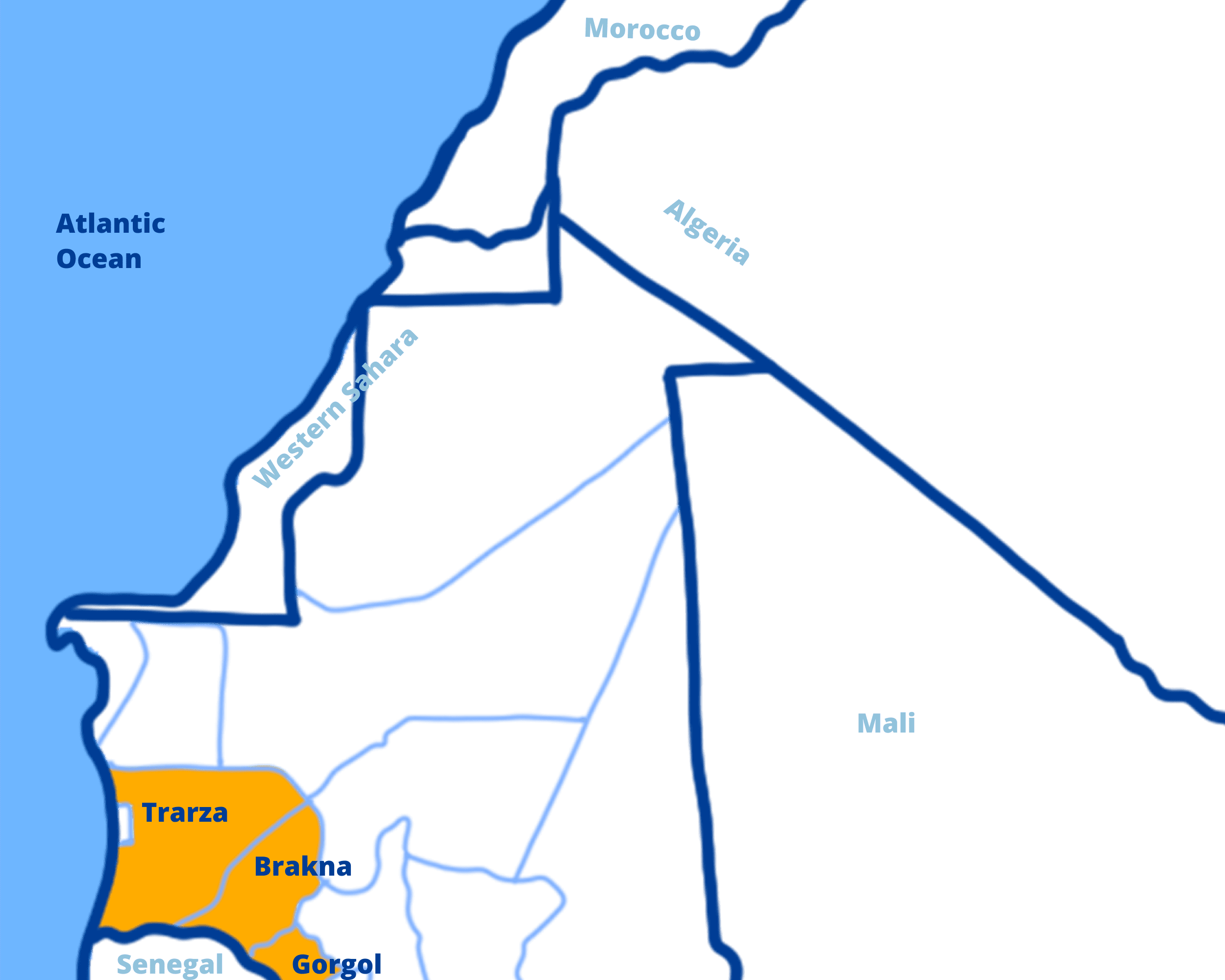

The conflict between these communities deterred development assistance, causing all groups to suffer sub-standard access to education, health care and irrigation. We intervene and collaborate with residents in three regions (formerly four): Traza with a focus on Rosso; Brakna with a focus on Bogue; and Gorgol with a focus on Kaedi.

In addition to this complex domestic reality, Mauritania faces other regional challenges due to its Sahelian location. The Northern border with Western Sahara is a turbulent site, while recent events in Mali have increased refugee movement towards Mbera.

Finally, the impact of climate change and accelerating desertification makes Mauritania increasingly vulnerable to food insecurity and resource scarcity. In short, Mauritania is a country vulnerable to climatic change. Building resilience and social cohesion at both local and national levels is key to ensuring a stable future.

-

Concordis is committed to working with communities to help them resolve their own problems. We believe this is more effective and much more sustainable than trying to impose solutions from outside, so we’ve trained and financed the work of 110 community mediators – local people who are well placed to help their communities find sustainable solutions to their differences.

We’ve been working in Mauritania in partnership with Mauritanian umbrella civil society organisation FONADH since April 2013 with funding granted by the European Union, the Allan & Nesta Ferguson Charitable Trust, German GIZ, the Government of Liechtenstein, the French Embassy, and the Worshipful Company of Arbitrators.

We undertake a number of activities in Mauritania’s southern communities. These include:

Promoting sustainable development and peaceful coexistence through inclusive dialogue between regional authorities, local communities and civil society actors;

Training a network of 110 Community Mediators from different ethnic groups, giving them the tools they need to resolve disputes between groups. From 2014 to 2018, with our training, Community Mediators have facilitated a total of 370 dialogues between disputing communities, enabling them to live together peacefully and to find consensus on their development priorities. These community dialogues aim to be as inclusive as possible and to further enable the participation of groups who would otherwise be marginalised from decisions affecting their lives, such as women and young people.

Facilitating high-level workshops in which civil society leaders and policy makers from all sides may work collaboratively to identify workable and mutually acceptable policy recommendations. These will address root causes of barriers to sustainable development and economic regeneration and will lead to sustainable development and economic regeneration.

Organising high level meetings with government authorities for the implementation of these recommendation.

Building Mauritanian civil society’s capacity, delivering the programme with and through them. For instance, we trained 72 people from the civil society in project and financial management, equipping them with the knowledge to set up small businesses.Their capacity-building will increase the sustainability of the programme beyond the term of Concordis’ funding.

Promoting good governance and sustainable livelihoods, by encouraging authorities to formally validate local action plans and peace agreements brought about through dialogue.

Advocating for and supporting local agriculture associations, especially women’s cooperatives, to further support a more sustainable management of communal and agricultural land.

Training local people in sustainable development and climate change sensitive techniques, in the sustainable and ecofriendly management of economic activities, and in the maintenance of local production, as well as in their own rights as citizens.

Starting a participatory study about women’s access to land ownership.

-

Disputes over land are notoriously difficult to resolve. Land is a finite resource and ownership of land is an emotive issue. Yet Concordis’ team in Mauritania has enabled local communities to find ingenious ways to resolve land disputes to their mutual benefit. Out of the 30 conflict sites in which we’re working, 19 communities have now signed agreements relating to the sharing of land and resources and 3 of these agreements were endorsed by the authorities, giving them force of law. Our work has also set a precedent: local residents in Goudiouma and Mafoundou, in Gorgol Wilaya, have settled recent contentions through peaceful dialogue and without the use of formal mediations.

We used a cartographer to map out the land in dispute, enabling the communities frame their arguments in concrete terms which, in turn, helped them find workable solutions. A cartography report, summarising the needs and interests of all sections of each community, is now being used to articulate those needs to the agencies with power to deliver solutions.

An evaluation of behaviour as well as social and economic relationships showed that, since the process started, the communities now have increased social interaction, make increased use of one another’s shops, schools and wells, and are more willing to share land and other resources.

We hosted eight high-level workshops, bringing together community leaders and national and international development actors to discuss the barriers to sustainable development and peaceful coexistence. This resulted in realistic, workable and mutually acceptable policy recommendations specific to each region, which were advocated to those with power to implement them.

We delivered many days of training for civil society leaders in Nouakchott and the regional centres. These have enhanced their ability to promote citizenship, democratic participation and access to justice in a way that will be for the benefit of all. To continue our work promoting economic development to mutual benefit, we believe building resilience to the effects of climate change and its impact on people and herds in the Senegal River Valley is vital. For more information, see our Cartography Report and our overview of current challenges in the Sahel and how climate change may be a major contributor to these.