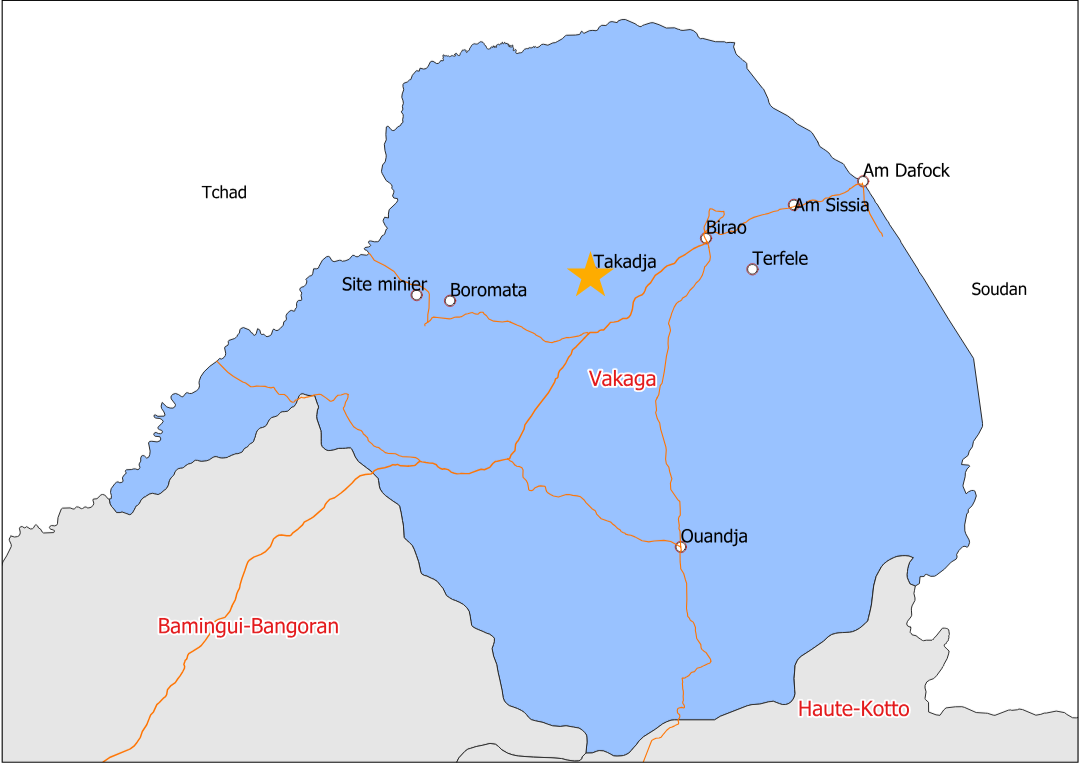

Changing the direction of escalating conflict: effective mediation in Takadja

On a hot Saturday in May, people in the village of Takadja, tucked into the remote northeast corner of the Central African Republic, near the Sudanese border, were going about their usual routines at the market.

It was the kind of day that, for all its simplicity, helped hold life together.

But beneath the surface, not everyone felt at ease. In addition to the upsurge in banditry in the area, news was spreading that some young men had been killed and, by nightfall, tension had taken hold of the village.

A serious incident was developing between the Taaisha (Arab) groups of South Darfur and the sedentary Gula communities in CAR.

What had happened was a robbery on the Boromata-Takadja axis – a nearby main road. A Gula motorcycle taxi driver was robbed by unidentified assailants. In response, the Gula mobilised a self-defence group of about one hundred men to track down those responsible. But as they pursued the robbers, this group was ambushed, and three men were killed in the attack.

In retaliation, that same self-defence group entered the market in Takadja, searching for those they believed were responsible for their members' deaths. They were convinced that members of the Taaisha ethnic group, who are of Arab origin, were responsible. In the market, they confronted two young Arab men who were trying to buy fuel. Tensions escalated quickly. Shots were fired, and both young Arabs were killed.

The Taaisha retaliation was not long in coming. Later that night, Taaisha men started to attack shops in the Takadja village. The situation worsened; the Taaisha took all the goats and donkeys from the Takadja market. MINUSCA arrested six Taaisha men in possession of automatic weapons, but many other armed youths began mobilising on both sides of the border.

In just 24 hours, suspicion and fear had created violence and loss for both sides.

Intervention by Concordis Advisory Group Members

Concordis has identified and trained trusted local peacebuilders from all the ethnic groups across northern CAR and South Darfur, supporting them as Advisory Group members. The next day, the Concordis team mobilised members of the Advisory Group on both sides of the border, including members from the Vakaga group from CAR and Taaisha members of Um Dafok group from South Darfur, in collaboration with the Islamic Council of CAR.

Omda Habib al-Tidjani, who is Taaisha and head of the advisory group in Um Dafok, travelled to CAR to mediate. He held talks with the Gula leaders to find an alternative to the conflict and persuaded the Taaisha youth, who had mobilised in CAR for revenge, to withdraw. Simultaneously, other members of the advisory group in Um Dafok intercepted the mobilizing Taaisha armed youths and persuaded them not to cross the border into CAR.

The team met with resistance too. The Taaisha leaders who arrived from Sudan were angry that the two innocent young men had been killed in the market and demanded blood money. In a tense standoff, the peace committee’s vehicle was seized.

After five days of peace talks in a mosque, responsibility was established and, after lengthy negotiations, the dia or blood compensation payable to the Taaisha was reduced from SDG 800 million (€1,100,000) to SDG 9.1 million (€13,300), with one-third to be paid immediately and the remaining two-thirds in June. Members of the Advisory Group then managed to persuade the Taaisha armed youths to disperse and return home and their vehicle was released.

In a region where trust is fragile and armed reprisals can ignite a cycle of violence, what happened could have been far worse. It was the joint actions of Advisory Groups on both sides of the border that avoided a deeper crisis, through dialogue and persuasion.

Why This Matters

The story of Takadja is not unique. In this part of the Central African Republic, decades of conflict have left behind deep divisions and communities struggling to trust one another. Disputes can easily flare into violence.

This situation has calmed, for now, but risks remain. There is still fear of reprisals, and places like local markets, which should be spaces of connection and coexistence, can easily become flashpoints without proper protection.

Beyond the mediation itself, there is urgent work to do: psychosocial support and material aid are essential for those affected by violence and looting. And with the planting season underway, it is essential people focus on farming, not fighting.

At the same time, it’s critical to address a growing sense of injustice, especially among settled communities who feel disproportionately pressured to pay compensation when conflict arises, as it often does with income nomadic groups. If these perceptions are not acknowledged and addressed, they risk fuelling resentment and undermining future peace efforts.

What happened in Takadja reminds us how fragile peace can be. But it also shows us that when trusted local peacebuilders lead the way, and when communities are given space to speak and be heard, peace isn’t just possible; it’s within reach.